Self-defense doesn’t end when the threat stops. That’s when the legal risk begins.

The US Law Shield app gives you immediate access to attorneys before mistakes are made.

Stand your Ground,Self-Defense Lesson & Underrreported News

The Story

“I Was Right” Isn’t a Defense

Marcus Hale owned a small printing shop on the edge of a North Carolina business park. He’d worked there for twenty years, usually alone by early evening, locking up around dusk. One night, just after closing, a former contractor named Eli showed up angry about a payment dispute that had already been decided in small claims court. Eli was shouting, pounding on the glass, and blocking Marcus’s path to his truck.

Marcus stepped back inside the workspace, heart racing. He told himself he was right—the court had ruled in his favor, and this was his business. North Carolina was a stand-your-ground state, he’d heard. He didn’t have to retreat. He reached into the desk drawer where he kept a lawfully owned handgun and chambered a round.

Eli forced the door open, yelling but unarmed, hands visible, closing the distance fast. Marcus raised the gun and fired, striking Eli in the shoulder. The shouting stopped, replaced minutes later by sirens and flashing lights.

Marcus kept repeating it to the officers: “I was right. He trespassed. Stand your ground.”

That’s where the mistakes began.

Under North Carolina law, stand your ground doesn’t mean stand whenever you feel justified. It requires a reasonable belief of imminent death or serious bodily harm. Eli was aggressive, but unarmed, and witnesses later confirmed he never threatened deadly force. Marcus had other options he ignored—calling 911 earlier, remaining behind a locked interior door, or disengaging entirely once Eli backed away after the shot.

Worse, Marcus escalated the encounter. He retrieved the firearm before Eli entered and made no clear verbal command to leave or stop. Investigators noted Marcus had moved toward the doorway instead of maintaining distance, undermining the claim that deadly force was necessary. Stand your ground removes the duty to retreat, but it does not remove the duty to act reasonably.

“I was right,” didn’t matter. Being right about the dispute didn’t justify the use of deadly force. Being angry didn’t create legal immunity. And owning a business didn’t turn a heated argument into a lethal threat.

In court, the prosecutor summed it up: " Stand your ground is a shield, not a sword. Marcus wasn’t convicted of murder, but the jury found the shooting unjustified. His business survived. His reputation didn’t. And the lesson followed him everywhere—self-defense law isn’t about winning an argument. It’s about surviving a threat without becoming the criminal yourself.

Most people focus on stopping a threat.

Smart people focus on preventing it from happening in the first place.

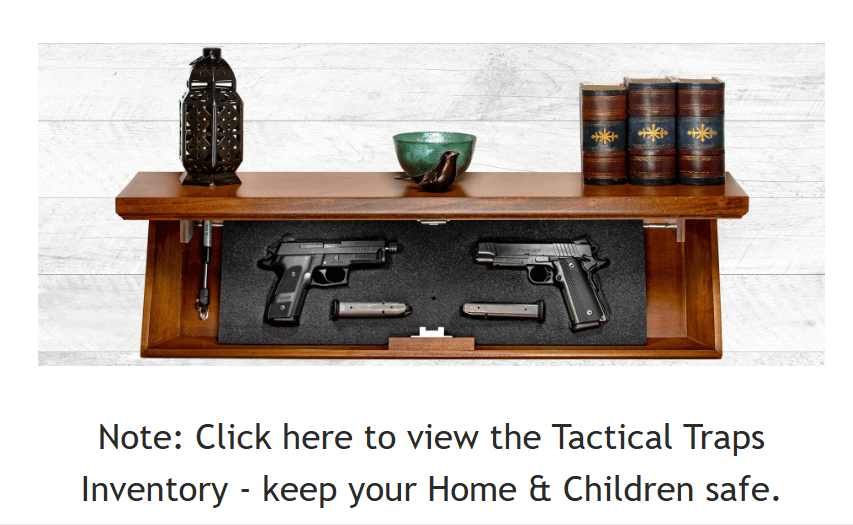

PSN recommends Tactical Traps because it works before stress, fear, or hesitation kicks in.

See how it works here, the ad itself.

Self-Defense Lesson: Position, Drop Step, and Forward Drive

Effective self-defense is not about strength, anger, or proving you were “right.” It’s about position, timing, and controlled movement. Three concepts—position of advantage, the drop step, and forward drive—form a practical framework for responding to real-world threats while maintaining balance, awareness, and legal defensibility.

Position of advantage means placing yourself where you can see the threat, protect your vital areas, and move freely, while limiting the attacker’s options. This is less about dominance and more about geometry. Angles matter. Distance matters. Obstacles matter.

In a workplace or public environment, a position of advantage often means keeping objects—desks, counters, vehicles—between you and a potential aggressor. It also means avoiding straight lines of attack and corners where your movement is trapped. A good position buys you time, and time is what allows better decisions, de-escalation, or escape.

The drop step is a simple but powerful movement: a short step back or slightly off-line while lowering your center of gravity. It is not a retreat born of fear—it’s a reset that improves balance and readiness.

By dropping your weight and shifting your lead foot, you reduce the chance of being pushed off balance, struck cleanly, or rushed. The drop step loads your legs like a spring, preparing you to move in any direction. Importantly, it also signals restraint. You’re creating space rather than closing recklessly, which matters both tactically and legally.

Forward drive is often misunderstood. It does not mean charging unthinkingly or escalating a conflict. It means controlled forward pressure when movement is necessary to escape, create distance, or stop an imminent threat.

Once balance and position are established, forward drive allows you to move decisively—through an opening, past an aggressor’s weak angle, or toward a safer exit. The key is intent: forward drive is purposeful, brief, and focused on ending the danger, not punishing the person.

When combined with verbal commands (“Stop,” “Back up”), forward drive can interrupt an aggressor’s momentum and create a moment to disengage. Used recklessly, however, it can turn defense into offense. That line matters in both physical survival and legal aftermath.

Underreported News: Crime Is Down—But Not Everywhere, and Not in Every Way

National crime statistics continue to point in a reassuring direction. Violent crime and property crime are down across much of the United States, particularly in large cities that dominated grim headlines during the pandemic years. Those numbers are real—and meaningful. But they don’t tell the whole story.

Beneath the surface of declining totals, latent crime trends are emerging in specific contexts, especially in places where incidents are less visible, less reported, or harder to categorize. These patterns rarely break through major news cycles, yet they shape how people actually experience safety in daily life.

One example is mass transit systems. While overall violent crime may be falling citywide, transit authorities and police departments have quietly reported increases in weapons detections—guns, knives, and improvised weapons—during bag checks, fare enforcement operations, and targeted patrols. Many of these incidents never become crimes on paper because no assault occurs. A weapon is seized, a citation issued, and the event disappears into administrative data rather than crime statistics.

To riders, however, the presence of weapons in confined public spaces feels like risk, not reassurance. The data may say crime is down, but perception is shaped by environment—and transit systems concentrate strangers, stress, and limited escape routes.

Another underreported area is street harassment and low-level intimidation, particularly in dense urban corridors and nightlife districts. Verbal threats, stalking behavior, aggressive panhandling, and unwanted sexual comments often go unreported. Victims frequently dismiss these encounters as “not serious enough,” doubt they’ll be taken seriously, or simply want to avoid further interaction with authorities. As a result, these incidents vanish statistically, even as they accumulate socially. Speech is an index into the mind- always remember this motto.

Experts note that modern crime reporting systems are better at counting completed offenses than near-misses or pre-criminal indicators. A firearm recovered before a shooting prevents violence—but also removes a data point that might otherwise signal rising risk. Likewise, harassment that stops short of assault rarely registers, despite its impact on public behavior and trust.

The result is a widening gap between official crime rates and lived experience. Policymakers point to declining numbers, while commuters adjust their routines, avoid certain routes, or change their work hours. Neither side is wrong—they’re just measuring different things.

Crime trends are not monolithic. They are situational, contextual, and unevenly distributed. A national decline can coexist with localized increases in weapons presence, intimidation, or disorder—especially in shared public spaces.

Understanding public safety in 2026 requires looking beyond headline numbers and asking harder questions: Where is risk concentrating? What behaviors are going unreported? And what signals are we ignoring because they don’t fit neatly into traditional crime categories?

Until those questions receive sustained attention, some of the most consequential crime trends will remain largely unseen—not because they aren’t happening, but because they don’t easily show up in the data that drives the news.

Prosecutors don’t care what you meant.

They care what they can prove.

Having legal coverage before anything happens matters.